Technically, we had been e-mailed an itinerary for our weekend excursion to the Bay of Islands. However, as I did not bring my laptop along, I found myself asking everyone else "When do we need to wake up tomorrow?" and finding out our activities as we did them. Fortunately, our first evening at the hostel was free of commitments. It consisted of sleep, going to a restaurant called Shippey's, which is on a boat, and then more sleep.

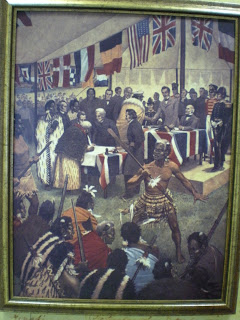

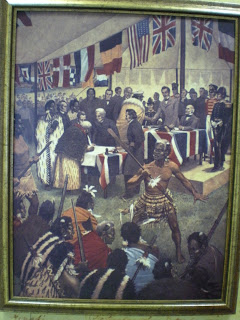

Saturday, the first real day of stuff, we went to the Waitangi Treaty Grounds, a place we've heard infamously much about in our classes. This is the place where, in 1840, British representatives and Māori leaders laid down guidelines relating to sovereignity and land ownership. The problem is, the Māori version--

Te Tiriti o Waitangi--is apparently quite different from the English version

--The Treaty of Waitangi. (Surprisingly, the Māori words

te and

o, which basically mean

the and

of, are not related to the English words. It's a small world--or a small mouth--after all.)

|

| A depiction of the treaty's signing. |

The Māori version says something like: you may keep all your land. Whereas the English version says something like: we may take all your land. It erupted in almost three decades of internal land wars. Naturally, this is still a point of contention today, though at the tourist-aimed Treaty Grounds, it was made to seem like all New Zealand is one big happy island family. Sort of like how in Pokémon all the creatures coexist happily and you never think about what that meat is the characters are eating.

|

| It really does take an extra mental step when viewing beautiful places to remember that war took place here. |

|

| A waka, or war canoe, replica built on the hundreth anniversity of the treaty's signing. Nowadays, waka can refer to any vehicle. There's even a bus company called Waka Pacific. |

Next on our trip was Russell, known as "The Hellhole of the Pacific" for the criminals, drunks, and sex workers who populated it in the days of yore. Upon arrival, we found, tragically, that it had devolved into a quaint seaside village.

|

| The Hellhole of the Pacific |

|

| Oh my god, get me out of this place. |

After going to the rather odd Russell Museum, whose bric-a-brac reminded my of an I Spy book, we were on our own to wander the town and beach. The beach was composed not of sand but of smooth rocks which groups of seagulls were nuzzling into for warmth. At the end of a beach was a surprise nature preserve trail.

|

| Though it said "Kiwi Zone," we saw no kiwis. They're nocturnal or some excuse like that. |

At the end of the trail we were left on a random road. All we knew is that we were high up and needed to get back down. On the way, though, we ran into an artist's collective and what we're pretty sure was a pukeko, another awkward bird which has waddled its way into New Zealand symbology.

|

| I did not take this picture. But you get the idea. |

|

| A bilingual pun at the art place. I went weak in the knees. (Aotearoa is the Māori name for New Zealand.) |

Oh, and speaking of awkward birds, as we were waiting for the ferry, we saw, no kidding, a one-legged seagull. I named him Skipper.

|

| He had to hop to move, but had amazingly good posture. |

In the evening, it turned out we were going back to the Treaty Grounds for a..."cultural performance and light show." But I mean, who's to say what authenticity is? At the end there was heart-warming a song in English about how the Treaty of Waitangi brought two peoples together to live as one. All the Dartmouth students were uncomfortable. It was great.

The next day, Sunday, I had the vaguest conception of beforehand. All I knew is that we were going further north, to Cape Rēinga, which it turns out is the very tip of the North Island.

Stop one was a place called Gumdiggers, which showed us places people used to dig for kauri gum, which is basically hardened sap from the kauri tree. Apparently it can be used in some type of varnish and lacquer and became New Zealand's biggest export in the 1900s. It's quite pretty, actually.

|

| Back in the day, the average New Zealand household had a piece of this lying around, usually as a doorstop. Now, at the gift shop, pieces this size sell for, oh, over a thousand dollars each. |

Then, some drive further, Cape Rēinga itself. The end of the world, or at least of land, for miles and miles.

|

| I couldn't help but blink in sheer awe. |

While everyone else went to look at a lighthouse, Melinda, Ian, Matt, and I took a path in the opposite direction toward Tapotupotu Bay.

|

| Suckers... |

|

| It felt like another universe. |

|

| A windy universe. |

So filled with rapture was I that I took a steep downhill path too fast running and lost my balance. I slid hard, still laughing. Even though I had sleeves and long pants, I was left with battle wounds.

|

| But really, what truer way of interacting with a place than being bodily altered by it? |

|

| Perhaps even destroyed? |

|

| A place that, were I to fall to my doom, I would comparatively not mind doing so in. |

After this, we were driven to some sand dunes where I learned we were going sandboarding! It's basically sledding, except with boogie boards, and headfirst, and sand doesn't melt if it gets in your eyes. It was an apocalyptic moment at the top of the dune, all of us students with our unwieldy boards, trying to keep them from blowing away or blowing us away in the fierce gusts. Sand whipped upward and battered our skin, and we were afraid to open our eyes. I went down at the same time as Genevieve and Rachel, and of course my board started steering off course toward them, and of course I wiped out in between their paths, and of course I fell over and got sand in my fresh wounds and in my eyes. I blindly staggered to the bus, unable to open my eyes until a lady with water helped me flush them out. Covered in sand and blood, I just had to smile. Indeed, it takes a lot to make me not have a good time. Maybe, I thought, I will be destroyed after all.

We rode back home along Ninety Mile Beach, which is actually only sixty-nine miles long, but dang that's still impressive. It's legally a national highway, you drive on the sand, and cops can catch you for speeding.

|

| Along the way in Opononi |

|

| Melinda went right to the shore. |

|

| !!! |

The next day involved a trip to the tallest extant kauri tree. Apparently trees much, much bigger existed when Europeans first came, but it wouldn't be the white man's burden if you didn't have to put your back into it, now would it?

|

| Tāne Mahuta, named after a Māori god, is up to 2500 years old and stands 168 feet tall. |

And then there was the Kauri Museum, which had a delightful mix of neat things and terrifying things.

|

| An unfortunate figure turning a crank. There's a button you press and he actually turns it, but it's the machine that moves, so his arm just follows lifelessly. Also, that position... And that face... |

|

| An old accordion. You were allowed to touch it! It still made noise! |

|

| Toys? Fun? |

|

| Poor things. |

And that's about the last thing we did before getting back to Auckland. Now for that paper I'm supposed to be writing about this trip that's due tomorrow...